|

About the Book

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

|

Part II: The Necessity of the Four

Gospels

Chapter 1

The Nature of Contradictions

IT IS MY purpose

in this chapter to set forth the nature of the evidence that

contradictions really do exist, that statements are made in one

part of Scripture which cannot by the ordinary laws of logic

be made to agree with other statements made in Scripture. But

I also want to show that these contradictions--far from undermining

the claim made by Paul when writing to Timothy that "all

Scripture is given by inspiration of God" (2 Timothy 3:16)

-- actually confirm the fact of inspiration in a unique and undeniable

way in every instance, except for one class which we shall consider

briefly under the first heading.

1. Contradictions which appear to have

arisen because of errors in transcription.

The majority of contradictions

in this category have to do with numbers. Despite all the research

by Hebraists from early Christian times to the present, we are

still not absolutely certain that we understand fully the system

of enumeration used in the Old Testament. The New Scofield Bible

states, in commenting upon I Chronicles 11:11, that there are

barely twenty-five cases where numbers in one part of the record

do not agree with those repeated elsewhere. Sometimes this is

clearly due to our failure to understand the system of reckoning

employed. Thiele's study, The Mysterious Numbers of the

Hebrew Kings, (1)

is an excellent example of how a proper understanding can bring

reconciliation where it had previously been thought impossible.

But some contradictions remain.

For example, in II Samuel 10:18 David is credited with having

destroyed 700 enemy chariots. In I Chronicles 19:18 the record

of the same event credits him with

1. Thiele, Edwin R., The Mysterious Numbers

of the Hebrew Kings, University of Chicago Press, 1951.

pg

1 of 14 pg

1 of 14

having destroyed 7000

enemy chariots. On this, H. P. Smith proposes that the difference

resulted from the desire on the part of a later chronicler to

enhance the extent of David's victory. On the other hand, of

course, since the Scriptures were copied by hand, the original

could have been misread. It could, in other words, be simply

a copyist's error. Curiously, people who have a low estimate

of inspiration are much more willing to attribute errors of this

kind to ulterior motives than to simple, unintentional mistakes.

It is ironic that Dr. Smith himself, when dealing with the text

of 2 Samuel 10:6 lists the number of Tob's fighting men as 1,200,

whereas the actual text says that there were 12,000! Was this

due to ulterior motives? Or was it perhaps not even Dr. Smith's

error at all, but the error of a typesetter? (2)

There are some extraordinary cases

of typesetting errors even in modern Bibles. I have an older

edition of the Scofield Bible. One day I noticed a typographical

error in the printing of Psalm 119; it has been corrected in

the newer edition. The reader will recall that this psalm is

divided into as many sections as there are letters in the Hebrew

alphabet. Each section is then headed with a Hebrew letter followed

by a conventional spelling-out in English of the way this letter

is pronounced. Curiously, in the older Scofield Bible, the section

headed by the word Yod (vv. 73-80), lacks the Hebrew character!

This is interesting because it is the one letter in the Hebrew

alphabet to which the Lord made specific reference in Matthew

5:18 when assuring his listeners that the Scriptures should never

fail. The jot of Matthew 5:18 is the missing Yod of

Psalm 119:73. Which only goes to show that with the best intentions

in the world -- and I am sure that tremendous care was taken

by the publisher -- omissions of this kind can occur. It escaped

the notice of everyone who had to do with the publishing of this

particular edition.

Sometimes such contradictions

appear to exist because the text has not been read with sufficient

care. Such a case is II Samuel 24:24 where a purchase involved

a price of 50 shekels of silver that in I Chronicles 21:25 reappears

as 600 shekels of gold. The purchase was made from a man whose

name is given in II Samuel as Araunah and in I Chronicles as

Oman. The two names are variants only and refer to one individual:

but the first account concerns only the purchase of a threshing

floor, whereas the second account has to do with a far

2. Smith, H. P.: quoted by E. F. Harrison,

"The Phenomena of Scripture," in Revelation and

the Bible, edited by Carl F. H. Henry, Baker, Grand Rapids,

1958, p.241.

pg.2

of 14 pg.2

of 14

more extensive piece

of ground which in due course became the temple court.

One needs to be very careful in

reading parallel accounts to make sure that there is not in reality

a significant difference in the circumstances. Richard D. Wilson

said that he once asked a man how many people lived in a certain

Southern city. (3)

The man told him there were 40,000. Subsequently he felt the

figure must be in error when he saw the size of the place and

so he asked a second man who told him that there were 120,000.

In due course he found that the population consisted of 40,000

whites and 80,000 blacks.

At times the huge numbers given

in Scripture for the number of camels, for example, or other

animals possessed by a man like Abraham are so large as to be

almost incredible and have likewise been attributed to copyists'

errors. But as we show in Part IV of this volume, there are very

precise modern parallels which suggest that no exaggeration whatever

is involved. Sometimes the number of dead after a battle seems

equally unbelievable, (4) yet one has only to read the travels of Marco Polo

to discover that battle losses of this order are by no means

unknown from earlier times, and enormous herds are still

owned by wealthy ranchers.

Others have questioned the numbers

involved in the ages given for the pre-Flood patriarchs. (5) But here again, there is

good reason to reserve judgment in the light of modern knowledge

and the predictions being made with increasing frequency by authorities

in the life sciences.

In concluding this brief survey,

it is important therefore to note first of all that some copyists'

errors do exist. But it is equally important to note that merely

because some particular number seems greatly out of proportion

to our way of thinking, we should not on that account assume

it is a copyist's error unless we have the means of checking

it against some other parallel part of Scripture which strongly

suggests that such an error does exist.

2. Contradictions which are more

apparent than real.

Because

this class of contradictions has steadily diminished as background

knowledge has increased, we do not need to spend much

3. Wilson, Richard D., Is the Higher Criticism

Scholarly? Sunday School Times Co., Philadelphia, 1922, p.53.

4. A brief but very useful article on this aspect of the problem

is found in Eerdmans' Handbook to the Bible, Eerdmans,

Grand Rapids, 1973, pp.191-92.

5. "Longevity in Antiquity and Its Bearing on Chronology," Part

I in The Virgin Birth and the Incarnation, vol.5 of The

Doorway Papers Series, Zondervan Publishing Company.

pg.3

of 14 pg.3

of 14

time upon it. However,

one example will be useful as an illustration.

In the New Testament we may note

that according to Mark 10:46, the Lord restored sight to a blind

man by the wayside as He was leaving Jericho; but according to

Luke 18:35, the miracle actually occurred as He was approaching

Jericho. The fact is that there were two Jerichos -- the

ancient one which was destroyed by Joshua and which would occur

at once to every Jew's mind as the Jericho; and a second

one situated about one and a half miles from the first one which

had been rebuilt by Herod and turned into a kind of summer residence

for Roman officialdom and would therefore be in the Gentile mind

the Jericho. Somewhere between the two, a blind man received

his sight. As is well-known, and as we shall have occasion to

explore in a slightly different way, Matthew wrote his Gospel

for Jewish readers, whereas Luke wrote his for Gentile readers.

This kind of "disagreement" when observed between the

three Synoptic Gospels is vitally concerned with an aspect of

revelation that is the subject of the last chapter. These contradictions

are certainly more apparent than real.

3. Contradictions which appear

to have resulted where there may well be a case of translation

from one language to another, as for example, where the words

of Jesus, presumably spoken in Aramaic have come to us through

the Greek.

It seems to me highly improbable

that the Lord spoke in Greek although it is certain that many

Jewish people in Palestine at the time were quite able to do

so. On a number of occasions we know indeed that the Lord used

Aramaic, since here and there His actual words are recorded in

that language (e.g., Mark 5:41). There is also good reason to

believe that Matthew's Gospel was originally written in Aramaic,

although the text we are familiar with appears in Greek and is

presumably, therefore, a translation of an original in Aramaic.

This raises the question as to

whether a translation has the same inspired authority as an original.

The usual answer to this is no. But in the present instance there

may be a rather special circumstance involved since Matthew himself

may in fact have been responsible for both the Aramaic and

the Greek versions. Was he inspired in the writing of both

of them? Some people believe that there is a numerical structure

to Scripture of a kind which they feel cannot be accounted for

except by assuming verbal inspiration; these persons hold that

this applies equally to Matthew's Gospel in the Greek Version

as it does to the rest of the New Testament. On this basis,

pg.4

of 14 pg.4

of 14

therefore, one must assume

that the Greek text of Matthew is equally inspired. On the other

hand, an Aramaic Version also exists,

(6) which may well have been the first

New Testament Scripture, an inspired account written expressly

for the dispersed Jews in the East who embraced the Christian

faith after the great gathering in at the Feast of Pentecost

(Acts 2:41).

Eusebius tell us in his History

of the Church (3:39) that one of the very early writers,

Papias, held that Matthew wrote or arranged the current sayings

of the Lord which had gradually accumulated by word of mouth

from those who had heard them firsthand, and set them forth "in

the Hebrew dialect", i.e., Aramaic. Irenaeus (Adv. Haer.

3:1) says that Matthew wrote an account of the gospel among

the Jews in their own dialect. Origen, according to Eusebius,

held the same view also. Jerome (see Catal. 3) says that

"Matthew composed the Gospel of Christ in Hebrew [i.e.,

Aramaic] letters and words, but it is not made out who it was

who afterwards translated it into Greek"; he adds, however,

that this text was preserved in his time in the Caesarean Library.

In the 1883 edition of the Schaff Herzog Religious Encyclopedia

under the heading "Matthew," the writer, after

discussing the relationship between this original Aramaic Gospel

of Matthew and the Greek edition, observes:

We prefer to hold to the opinion

that a Hebrew [i.e., Aramaic] Gospel of Matthew did exist and

that our canonical Gospel [i.e., the Greek one] is a reproduction

and enlargement of it by his own hand [emphasis mine].

It may seem

as though we are stretching a point unduly to suggest that Matthew

wrote his Gospel in Aramaic and then in Greek and that he was

equally inspired in both. Yet we have interesting examples of

both ancient and modern authors who wrote first in one language

and then translated their own works into another language. Inspiration

was lacking in these examples, of course, but the circumstances

are much the same and show that such a thing is possible. Josephus

wrote his Wars of the Jews in Aramaic and then rewrote

it in Greek. (7)

More recently, a Hebrew scholar, A. S. Yahuda, wrote a learned

work on the Old Testament first in German

6. Matthew's Gospel in Aramaic: see an interesting

discussion of this matter by Asahel Grant, The Nestorians,

Murray, London, 1841, pp.168f. The author believes that these

people were remnants of the tribes taken into captivity who did

not go back to Palestine. See also J. E. H. Thomson, "The

Readers for Whom Matthew wrote his Hebrew Gospel," Trans.

Vict. Instit. 54 (1922):178-99. Thomson believes that the

Aramaic Gospel of Matthew is not merely a translation of the

Greek but an independent version.

7. Josephus' Wars of the Jews in two languages: see J.

E. H. Thomson, ref. 6, p.179.

pg.5

of 14 pg.5

of 14

and then in English.

(8)

The latter admits freely that he

found it difficult merely to translate his own work, and the

result was that he set forth exactly the same information but

recast in a more appropriate form for the second language. Thus

some of the reports which Matthew gives us of the Lord's words

spoken originally in Aramaic have, still under divine inspiration,

been preserved for us in Greek--and presumably, therefore, in

a form which is not precisely their original one. What we have

is not the kind of transcript of the Lord's words which a tape

recorder would have left us, but rather that kind of record which

the Holy Spirit was pleased to give us through the instrument

of a man's mind translating as he wrote. There is no need to

abandon verbal inspiration even though the actual words that

appear in the Greek text were probably not the actual words spoken

by the Lord. By avoiding a slavish insistence upon the recording

of His precise words, the text we have provides us rather with

an enlarged insight into what the Lord was telling us.

Matthew's Aramaic Gospel was written

for dispersed eastern Hebrew Christians to whom Aramaic

was most familiar. Presumably his Greek version was written for

western Hebrew Christians dispersed around the Mediterranean,

to whom Greek was more familiar. As a matter of fact, the existence

of the Aramaic version seems to have been almost unknown to the

latter. As a consequence, Matthew occasionally reports sayings

which incorporate some of the original words (assuming that even

Greek-speaking Jews would be familiar with them). For example,

when our Lord rode triumphantly into Jerusalem the people said,

"Blessed is He that cometh in the name of the Lord; Hosanna

in the highest" (21:9). In reporting this same incident,

Luke tells us that the people said, "Blessed be the King

that cometh in the name of the Lord: peace in heaven, and glory

in the highest" (19:38). Of course, it is possible

that some said one thing and some another; but it seems to me

equally likely that Matthew, well aware of his readers' Jewish

background, could afford to use the word Hosanna, whereas

Luke, who was similarly aware of the background of his Gentile

readers, would avoid an Aramaism and use a word equally appropriate

but much more intelligible to them. Luke was still divinely overruled

in his choice of the equivalent word, and plenary inspiration

is just as necessary to ensure this.

In his introduction

to The Gospels from the Aramaic, George M.

8. Yahuda, A. S.: referred to by D. M. McIntyre,

"The Synoptic Gospels and Their Relation to One Another,"

Trans. Vict. Instit. 65 (1933):123.

pg.6

of 14 pg.6

of 14

Lamsa (9) suggests that there are a few places where a statement

is made by the Lord according to our Greek texts which would

be more meaningful if we assume that the original Aramaic was

misunderstood by some transcriber into Greek. It seems possible

that a number of the Lord's sayings were preserved orally by

the disciples in their original form, and that people like Luke

sought out these personal recollections and incorporated them

into his manuscript. There is no reason why this should not have

been true in the New Testament as it was in the Old Testament,

whence a number of then-existing documents were quoted to form

part of Scripture, which documents have long since disappeared.

The Book of Jasher, for example, is referred to in connection

with Joshua's long day. Luke may have made use of some of many

well-known sayings of the Lord. Lamsa suggests that the word

camel is rather like the Aramaic word meaning heavy

rope, and that it was this to which the Lord made reference

as being "difficult" to thread through the eye of a

needle (Luke 18:25). I am aware there are some who believe that

one of the small gates in the wall of the city was referred to

as "the eye of a needle," imposing a similar problem

for the camel driver.

Another example may possibly be

found in connection with the Aramaic word for "talent."

By a very small slip of the pen, this could be mistaken for the

Aramaic word which means "a province." Thus in Luke

19:13, 17, and 24 it is conceivable that what the Lord really

said to the man who had invested his talent successfully was

that he would be made responsible, not for more "cities,"

but for more "talent." According to Lamsa the two words

may be so written that only the placing of a single dot distinguishes

between them. I'm not sure how true this surmise really is, but

it is worth noting. Yet I must confess that this kind of explanation

makes me uneasy because, rightly or wrongly, I feel that it challenges

the rather necessary assumption that our Greek text has been

preserved faithfully. It is true that we do have some

cases where variants occur, and alternative readings do exist.

But in these two cases there is no such textual evidence. It

is simply human surmise with no documentary evidence to support

it.

Furthermore, there are a

number of cases in the Gospels where a conversation is reported

by two different authors. The wording is often not precisely

the same in the two reports. The change can be in word order

and sentence structure or in vocabulary. Simple omissions

9. Lamsa, George M., The Four Gospels According

to the Eastern Version, Holman, Philadelphia, 1933: camel

vs. cable, p. xi; talent vs. province, pp.xif.

pg.7

of 14 pg.7

of 14

of words in one report

need not trouble us. But when different words or sentence structure

are used, we have a problem. Does verbal inspiration mean that

a particular statement made by the Lord must always be set forth

identically as a tape recorder would reproduce it? Or is it sufficient

that we have the sense of what the Lord intended? If this

is allowable, could it not be that verbal inspiration relates

rather to the inspired purpose of each evangelist in presenting

his record? The choice of actual words would then be subservient

to the plan of his Gospel and the background of his readers,

but still divinely inspired. The multifaceted meaning and significance

of the Lord's recorded conversations would be faithfully preserved.

The Holy Spirit therefore overruled

the choice of words which each Gospel writer employed so that

exactly that message would be conveyed which was required to

communicate the truth to each group of readers. Thus we have

to free ourselves of the idea that a tape-recording of the actual

words used by a man is of greater importance than what he is

seeking to communicate. I am persuaded that every word which

Jesus uttered was in fact so pregnant with meaning that it was

simply impossible to set it forth as a simple verbal transcript.

His sayings have come to us through several minds, each of which,

receiving the same original utterance, filtered and distilled

it under divine inspiration so that more of its depth has come

through to us by reason of apparent contradictions (and

not in spite of them) than could possibly have been communicated

in any other way.

In the section that follows, and

indeed in the rest of this paper this important truth is first

of all illustrated from Scripture and then explored in the light

of what we now know about the means by which we communicate to

one another the truths we perceive.

4. Contradictions occurring in

reports by individuals who are independently setting forth what

was said or what was done, and whose disagreement does not

arise because of the use of a different language but for

some other reason which appears to render the contradiction

in no way accidental but entirely by design.

From what has been said thus far,

the reader will gather that I'm not greatly in favor of so-called

harmonies of the Gospels. To my mind, it is analogous to taking

three or four photographs of one individual from slightly different

angles and attempting by superimposing the negatives over one

another to print a single picture. Unless they are all precisely

the same, the final portrait would be far less clear and meaningful

than any one of the originals taken singly.

pg.8

of 14 pg.8

of 14

Yet the originals are

all genuine portraits of the same person and cumulatively add

up to a total view. There is, of course, a difference in the

present context between a visual portrait and a "portrait"

drawn in words. To this extent, the analogy is quite unfair,

because we assume that if someone said something, there is only

one way of "accurately" recording what he said -- no

matter from what angle we approach the speaker. That is, we make

a faithful transcript of his words.

This is a reflection of Western

man's peculiarly developed sense of truth, which stems rather

largely from our tremendous dependence upon a written text. Whether

a man means what he says doesn't seem to us as important as the

actual words he uses. So you often hear someone in an argument

complain, "But you said..." To which the reply generally

is, "But that's not what I meant...." Thus, while we

give lip service to the principle that what we mean is more important

than the words we use, we are still persuaded that a man's actual

words must at all costs be transcribed rather than his intended

meaning.

This places us in an embarrassing

position. If we argue strongly for verbal inspiration (I'm thinking

of the Gospels at the present moment), we are at the same time

being forced to acknowledge that the Lord's statements are often

differently reported by different writers. Some must therefore

have reported incorrectly? If we impose upon God our own

insistence that truthful reporting is limited to the recording

of a man's actual words, then we are forced logically to admit

that in many places the Gospel records were not verbally

inspired--because the fact is that the Gospel writers often do

not agree upon the words He actually used. But if we once recognize

the fact that it is the Lord's meaning that is of fundamental

importance, then we are free to allow the Holy Spirit to put

into any Gospel writer's mind just those words which will preserve

for us intelligibly exactly what the Lord intended by them. And

since His meaning was always so much more far-reaching than any

single mind could comprehend, what He was communicating in His

conversation had to be set forth in several different ways. And

to be absolutely certain that in this transcription no error

in meaning would be introduced, the Holy Spirit inspired the

words that were to be used by each Gospel writer in his report.

So it has come about that what to our superficial way of thinking

may appear as very loose or even contradictory reporting is actually

an essential part of the inspiration of Scripture. In this sense,

contradictions are a necessary part of revelation.

pg.9

of 14 pg.9

of 14

It may be argued that

in some instances we must not suppose contradictory reporting,

but rather that the statements of each of the Gospel writers

are to be put together in order for us to recover the whole truth.

An analogy is to be observed in the inscription on the cross,

where the total wording may be recovered by combining what each

writer has recorded. In Matthew 27:37 the inscription is stated

as follows: "This is Jesus, the King of the Jews."

In Mark 15:26 it appears as "The King of the Jews."

Luke 23:38 has it, "This is the King of the Jews."

And in John 19:19 it is given, "Jesus of Nazareth, the King

of the Jews."

There are two ways in which one

can deal with these four accounts. The first is to say simply

that each writer was led to pick upon only part of the total

inscription, the part he recorded being appropriate to the purpose

of his Gospel. Putting them all together produces the following:

"This is Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews."

Out of this total inscription one can extract any one of the

four Gospel accounts. They are, therefore, in this light assumed

to be additive. The second alternative is that since the title

was written, as we are told specifically, in Greek and Latin

and Hebrew, the wording adopted by each Gospel writer was that

which appeared in the language most familiar to him. Matthew

recorded what was written in Hebrew, Mark in Latin, and Luke

in Greek. It is also possible that the total inscription was

in all three languages, but this seems to me a tattle less likely.

John, writing somewhat later in time, comes nearest to putting

down the total inscription.

One further point in the same connection

is worth noting. Matthew, seeing the situation through the eyes

of a Jew and writing for Jewish people, refers to the inscription

as an "accusation." Luke writing for those who would

hardly see the significance of the inscription in these terms,

simply refers to it as a superscription. Mark, who wrote for

the Romans, notes that it was both a superscription and an

accusation. John, who saw perhaps more clearly with the passage

of time, looked upon these words as having much greater significance

than merely standing as an accusation or a superscription. He

refers to it as a "title."

I believe that this principle of

adding together cannot be applied in more than a few cases except

by some rather artificial reconstructions. However, one or two

further examples may be worth observing. For instance, Matthew

15:28 reads "Jesus answered and said unto her, O woman,

great is thy faith: Let it be unto thee even as thou wilt...."

At this point we may add Mark 7:29 which reads, "For this

saying go thy way; the devil is gone out of thy

pg.10

of 14 pg.10

of 14

daughter." And

the record is then completed by Matthew: "And her daughter

was made whole from that very hour." Additively, Matthew

and Mark give us a complete picture.

Another case is found at the time

of Jesus' trial, in the following way:

Matthew 20:19: "mocked..."

Luke 18:32: "...and spitefully entreated and spitted on."

Matthew 20:19: "...and scourged."

Clearly there

is no contradiction of fact here, so this is not what I mean

when I speak of contradictions. What I do mean is illustrated

in the following. In speaking to the Pharisees and other religious

authorities, Jesus said, according to Matthew 26:55, "Ye

laid no hold on Me." According to Mark 14:49, His words

were, "Ye took Me not." According to Luke 22:53, He

said, "Ye stretched forth no hands against Me." It

is clear that if any one of these is reporting accurately, as

we commonly define accurate reporting, then the other two are

reporting inaccurately. That each of these sentences has fundamentally

the same meaning is quite evident, however, and since I personally

believe in verbal inspiration, I am convinced that each writer

was inspired to record the Lord's words as he did. I think we

must assume in that case that in some way which may not be immediately

apparent, the difference in wording was deliberately chosen by

the Holy Spirit to preserve the unique character of each of the

Gospel portraits as a whole. In some cases, which we shall return

to in the last chapter, we can see why there were differences:

in this particular case the reason is not clear to me at the

moment, but I am certain that there is a perfectly good reason.

Here is another example.

In Matthew 21:2, which has to do with the Lord's commission to

certain of the disciples to go and bring the ass upon which He

was to ride into Jerusalem, Matthew records His words as having

been "straightway ye shall find..."; Mark (11:2) "as

soon as ye be entered into it, ye shall find...; and Luke (19:30):

"at your entering ye shall find..." Clearly these are

the same statements in intent, and equally clearly they cannot

be merely added together to evade what appears, superficially,

as contradiction. The Greek text is not precisely the same in

each case. If these purport to record the identical conversation,

we must assume that the strict recording of words has

been replaced by a reporting of intention because this

was of greater importance.

We have another such example in

Matthew 19:26, where the Lord's words are given as "With

God all things are possible." Luke

pg.11

of 14 pg.11

of 14

18:27 records this same

statement in the form, "The things which are impossible

with men are possible with God."

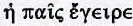

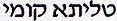

The next illustration shows precisely what

I mean. In Mark 5:41 (in the Authorized Version), Jesus is said to have

raised Jairus' little daughter with the Aramaic words, "Talitha

cumi." Luke 8:54 gives the Lord's words on the same occasion

as having been "he pais egeire" (in the Greek  ). No person could possibly use these two

entirely different speech patterns at the same time, although they both

mean the same thing--"Maiden, arise"--the first is Aramaic

( ). No person could possibly use these two

entirely different speech patterns at the same time, although they both

mean the same thing--"Maiden, arise"--the first is Aramaic

( ) whereas the

second is Greek. It is reasonably certain that Jesus used the former words,

since He spoke Aramaic. The Holy Spirit who inspired the writing of both

Mark's and Luke's accounts clearly intended us to know the meaning

of Jesus' words rather than the sound of them. ) whereas the

second is Greek. It is reasonably certain that Jesus used the former words,

since He spoke Aramaic. The Holy Spirit who inspired the writing of both

Mark's and Luke's accounts clearly intended us to know the meaning

of Jesus' words rather than the sound of them.

There are many occasions upon which

the general intent is the same, though the way the intention

is expressed is deliberately different. In Matthew 18:8 the Lord

is reported as saying, "If thy hand or thy foot offend thee,

cut them off." But Mark 9:43 reports these words

as "If thy hand offend thee, cut it off." The quotation

from Mark includes no reference to the feet. The rest of each

of these two sentences makes it clear that the omission is intentional:

Matthew continues, "It is better for thee to enter into

life halt or maimed, rather than having two hands or two feet

to be cast into everlasting fire"; Mark finishes the verse,

"It is better for thee to enter into life maimed than having

two hands to go into hell."

It seems unlikely that these two

passages are intended by the Holy Spirit to be combined in the

way that we might combine Matthew 15:28 and Mark 7:29 (referred

to earlier). In the former case a combination adds to our total

understanding, whereas in this case nothing is added. On the

other hand, if--as I shall try to show in the last chapter--Mark

was laying emphasis upon the Lord as an exemplary Servant, then

it may well be that the stress is upon the servant's hands rather

than upon his feet. A lame servant could still be a good one;

but from the point of manual labor--that is, for service as we

ordinarily think of it--a servant without hands is virtually

useless. Thus, possibly the omission here is deliberate and is

in keeping with the special object and character of Mark's Gospel.

One further illustration of contradictory

reporting is to be found by comparing Mark 5:19, 20 with Luke

8:39. This is an account of the healing of the maniac of Gadara,

who desired immediately to become part of the Lord's entourage.

However, Jesus Suffered him not, but said to him, "Go home

to thy friends, and tell

pg.12

of 14 pg.12

of 14

them how great things

the Lord hath done for thee." Luke puts the Lord's

instructions as follows: "Return to thine own house,

and show how great things God hath done unto thee."

There is disagreement in the instructions, in the one case to

go home and tell his own friends, and in the other to tell his

own house. But even more important, there is this divergence

in wording by the use of the word Lord as opposed to God.

There is no contradiction in meaning: but there is in terms

of the actual words spoken. If we insist that the only truthful

reporting is what a tape recorder would provide, then which word

would the tape have recorded? I think it is also worthy of note

that the healed man, according to Mark, went home and began to

publish how great things Jesus had done for him. Mark makes no

attempt to excuse the man for his disobedience, for in point

of fact he was not being disobedient, since Jesus is indeed both

Lord and God (John 20:28).

I cannot refrain from referring

in this context to Luke 17:16, the story of the healing of the

ten lepers. One of them returned to say, "Thank you."

Luke records what happened: "When he saw that he was healed,

he turned back and with a loud voice glorified God, and fell

down on his face at His feet, giving thanks." It

seems to me that unless one makes the assumption that Jesus is

God, the writer would have been led to make it quite clear that

the feet were not God's feet. The fact is that they were the

feet of God.

It will be noted that these contradictions

in reporting chiefly concern words spoken by the Lord. I have

not made an exhaustive study of the evidence, but my impression

is that when Scripture reports the words of man (for example,

Matthew 11:3 and Luke 7:20: John the Baptist speaking), this

kind of free paraphrasing is not allowed. In short, the words

of men are reported consistently without contradiction because

such words never have the inexhaustible content of meaning as

the words of God have. Even when the Lord Himself is quoting

what man has said, He quotes the words precisely (cf. Matthew

11:19 and Luke 7:34).

As we shall

see, it is often quite as important to note what is omitted as

it is to observe what is included. Matthew frequently judges

the Jewish people very harshly and does not hesitate to set forth

the severest strictures which Jesus pronounced against His own

people. By contrast, the other writers are more gentle and omit

many of these strictures. Evidently it seemed proper to the Holy

Spirit that one who was not writing to the Jewish people specifically

should not be encouraged to emphasize their wrongdoing; but in

Matthew's

pg.13

of 14 pg.13

of 14

Gospel written for Jews

by a man who was himself one of their number, it was not appropriate.

Enough has therefore been said

to establish the fact that there are clearly contradictions in

reporting which the Holy Spirit has not merely allowed

to appear in the text, but has, to my mind, deliberately introduced

because by them something more has been revealed than would have

been impossible by slavishly repeating on every occasion the

same precise wording. Every attempt to remove these inconsistencies

by artificially combining them or by excusing as errors of transmission

inevitably robs us of part of the total revelation which God

intended. For this reason I believe harmonies of the gospels

can be dangerous. In fact, experience shows fortuitously that

they never have been successful in any case.

While we thus say that the meaning

is the important factor, it is still true that meaning cannot

be conveyed without words. Thus it needs to be underscored that

to give the true meaning according to the mind of the Holy Spirit,

inspiration of the wording was required. This is all the more

essential where the record is apparently contradictory.

pg.14

of 14 pg.14

of 14  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next Chapter

|